Erik was told that his second great-grandfather, Hugo Kamp, came to America by smuggling himself on a cargo ship traveling from Germany to New York. He was born circa 1873 in Germany where he worked as a knifemaker before he moved to New York City in 1903.

The Research

In researching other families, I have previously seen notes at the end of passenger lists giving the names of passengers who were on the ship but did not pay the fare. I thought it would be interesting if we could find this type of record for Hugo. I did a search of the New York Passenger Lists and here is the first document I found:

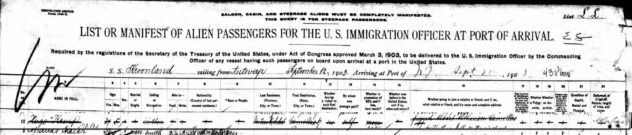

Passenger List Entry for the S.S. Kroonland Showing Hugo’s Name Crossed Off on 21 September 1903 (Click to Enlarge)

There is an entry for Hugo, but the entire line is crossed off. This may seem odd, but keep in mind that passenger lists were written before the ship left the port of departure. When a person is crossed off from a passenger list, it typically means that they did not get off the ship at the port of arrival. This could be a variety of reasons perhaps they missed the boat, got off at a different port, were too sick to travel, or lost their tickets at the last minute during a poker game. What we know from this list is that Hugo was supposed to arrive in New York on 21 September 1903 aboard the S.S. Kroonland, which departed from Antwerp, Belgium on 12 September 1903. His last residence was listed as Widdert in the Solingen Region of Germany. This city is also known as “The City of Blades” for the large number of knife, sword, and razor blade manufacturers in the area. This makes sense because his given occupation was a “cutler.” He did pay for his ticket and had over $50 with him when his name was written on the departure list. However, if you look closely, there is a small note at the end of the entry which states that he was not on board when the ship arrived in New York.

Note in the Right-Side Margin on the Above Passenger List (Click to Enlarge)

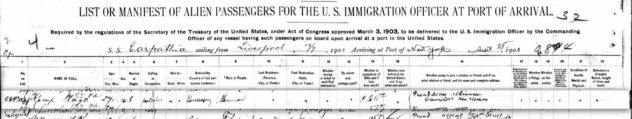

We did find another passenger list for just four days later, which shows that Hugo arrived in the Port of New York on 25 September 1903. This time he departed from Liverpool, England and boarded the S.S. Carpathia (yes the same ship that would later rescue passengers from the sinking Titanic in 1912). Hugo was born in Germany, but his last residence was listed as in Antwerp, Belgium. This time he only had $24 on him, and his final destination was to a friend, Alton Althousen who lived in Camillus, Onondaga County, New York. The record also shows that he did pay his own passage.

Passenger List Entry for the S.S. Carpathia Showing Hugo’s Arrival on 24 September 1903 (Click to Enlarge)

Another thing to note is that in the margins you can see letters S.I. written next to his name. This means that he was held for a Special Inquiry to determine whether or not he is eligible to immigrate to America.

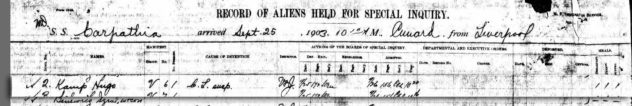

I also found a register of passengers who were detained for Special Inquiry from the Carpathia on this same day. The entry for Hugo shows that he was held for a day (from the 25th to the 26th) for suspicion of Contract Labor.

Entry for Hugo Kamp on the List of Immigrants Held by the Board of Special Inquiry from the S.S. Carpathia (Click to Enlarge)

He was detained because it was suspected that he would be in violation of the Alien Contract Labor Law, also known as the Foran Act, initially passed in 1885. This law prohibited American employers promising immigrants a contract for work once they arrived in the United States. The goal of this was to prevent aliens from taking jobs away from American citizens by discouraging employers from taking advantage of the less expensive labor pool of new immigrants. It was largely in response to the influx of Chinese labor in the rapidly developing West Coast, but in this case, it also applied to a skilled worker who had a job lined up at a cutlery manufacturer in Central New York.

Advertisement for the Camillus Cutlery Company, published in the American Culter April 1922 Vol. 154

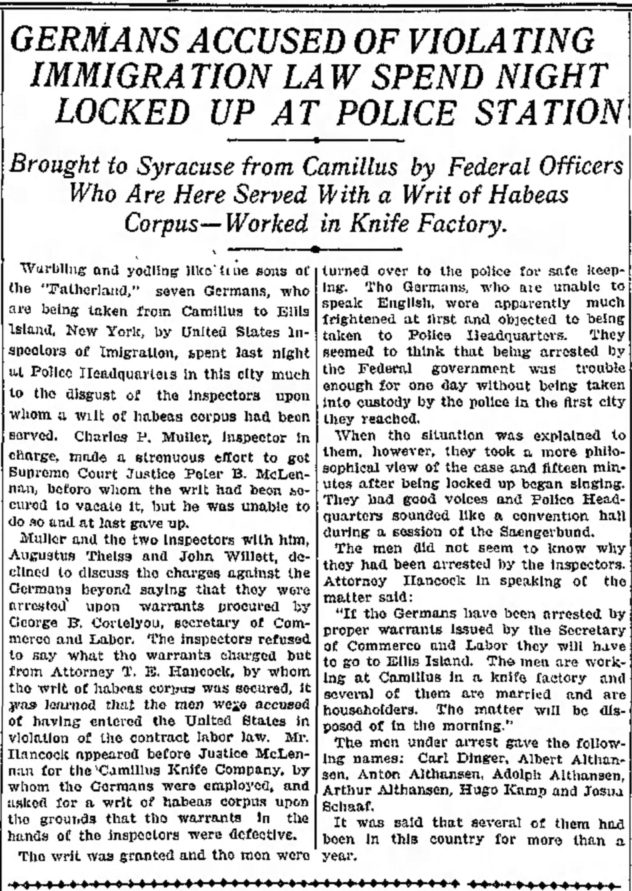

Once Hugo was released from the special inquiry he went to start his new life in Camillus, New York working at the knife manufacturer The Camillus Cutlery Company, but his troubles with immigration weren’t over. Less than a year later, on 16 April 1904, Hugo and six other employees were taken into custody by the police in Syracuse, New York and detained overnight before they were to be transported back to Ellis Island for violating contract labor laws. According to the article published in the Post-Standard, the officers at the local police force were reluctant to take the men in and urged the Supreme Court Justice to vacate the order. Apparently, the Germans were at first scared of their apprehension in Syracuse, but once they realize what was going on they relaxed and began to sing in their jail cell. The article stated that the “warbling and yodeling” Germans made the city jail sound “like a convention hall during a session of the Sangerbund.” It’s also interesting to note that Hugo was arrested with Anton Althousen (and two of his brothers), who he listed as his final destination on his passenger list, and Josua Schaaf, who arrived in New York with Hugo aboard the Carpathia and was also held on a special inquiry for violating the contract labor law.

Article Detailing Hugo’s Detention Published in The Post-Standard (Syracuse, New York) on 16 April 1904

Hugo and his coworkers were held in New York for a month and then on 27 May 1904 the Germans caught a break when it was ruled they could not be charged and deported for contract labor because they were already found innocent and admitted by the Board of Speical Inquiry upon their arrival in 1903.

The Verdict

Erik’s granny is a liar! Hugo paid his way to immigrate to America aboard a passenger ship in 1903 and did not hide away on a boat. He did run into some legal troubles because he was a skilled foreign worker who came to the United States to work at a German company that made knives. It was suspected that he came to the America with the promise of employment there. What interesting about Hugo’s story is that it is true that he did have issues with immigration after arriving in America, but later that seed of truth turned into a more interesting family legend.

Research Notes

To learn more about digging deeper into passenger lists, the JewishGen site has a lot of great information about deciphering the marking on passenger lists, including a guide to reading the annotations on passenger manifests and abbreviations for those held on Special Inquiry.