After over a year-long hiatus Is Your Granny a Liar? is back with a knock out family legend!

The Story

Erin was told that she had a relative that was the manager of boxers during the last wave of bare-knuckle fights in Brooklyn at the turn of the nineteenth century. He went by the name “Broadway Bill” Wakely, and he was good friends with Damon Runyon – a famed newspaper man. Bill also owned a bar in New York at the corner of 6th Avenue and 42nd street. The family legend is that he had gained quite a fortune managing the boxers. However, he lost it all when he backed the wrong fighter and ended up leaving his family with no inheritance. At the end of his life, Damon offered to hold a fundraiser for the ailing Broadway Bill, but his “lace curtain Irish” family turned down the offer since Bill was the black sheep of the family.

The Research

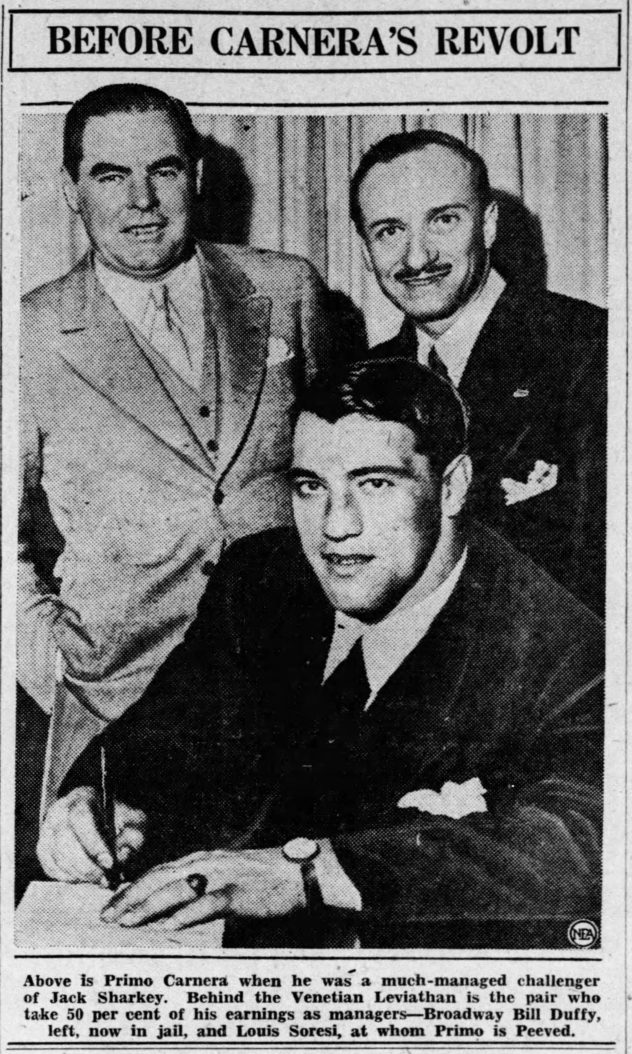

“Big Broadway” Bill Duffy

My resources showed that bare-knuckle boxing was popular in Brooklyn and New York City during the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. I was able to find a man called Broadway Bill, who was the manager of the famed fighter Primo Carnera. Primo’s towering height of 6′ 7″ earned him nicknames such as the Ambling Alp, the Venetian Leviathan, and the Monster.

Broadway Bill Duffy (occasionally called Big Bill Duffy) was known for being a bootlegger in the 1920s. After prohibition, he was involved with racketeering with the mob in Brooklyn. He owned several bars with salacious names, such as Silver Slipper, Frivolity, Rendezvous, and Bill Duffy’s Old English Tavern. These shady activities landed him in prison several times. His first offense came as a juvenile for theft, and in the 1910s he did time in Sing Sing for robbery. In the 1930s, his racketeering finally caught up with him, and he was sentenced in federal court for tax evasion. It was during this time his deal of managing the prized fighter Primo Carnera fell apart. After his last stint in prison, he moved to Long Island where he lived with his family until his death in 1952.

Some of the details of the story lined up, but I couldn’t find any connection to a Wakely family or Damon Runyon. Also, this seemed to happen a little later than I was expecting as most of Bill’s involvement in the boxing management occurred in the 1920s and 1930s — a time when professional boxers were legally required to wear gloves. Finally, I couldn’t find any evidence that he owned a bar on 6th Ave. at 42nd Street. As such, I don’t think this is the right guy, so I decided to keep looking focusing more on the Wakely surname.

James “Jimmy” Wakely

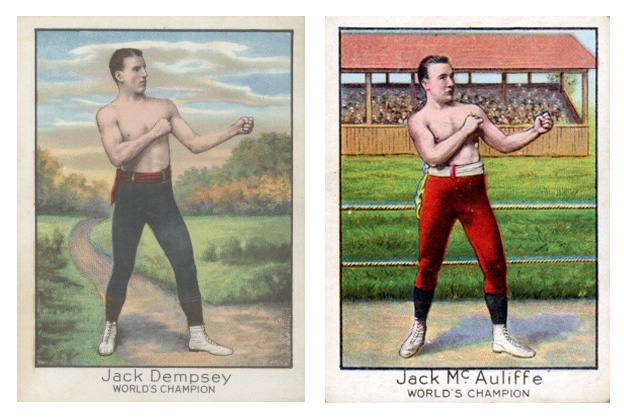

The next promising article I came across tells of a competition between two pugilists, Jack Dempsey, and Jack McAuliffe. The two men were not going to fight with their fists, but rather they would hold a contest to see who could make the most barrels in a given amount of time. Both men had worked together as coopers, or barrel makers, before leaving to be professional prizefighters. Dempsey bragged that “there wasn’t a better cooper in the city of Brooklyn” and eventually they wagered $100 paid to Jimmy Wakely, the proprietor of the saloon at on 6th Ave. and 42nd street. The competition was set to take place in a week from the publication of the newspaper article, but I never found a followup and it’s possible Jimmy just kept the $100.

The competing coopers Jack Dempsey and Jack McAuliff on Cigarette Cards circa 1910

Jimmy Wakely seemed like a much more likely connection to Erin since he did own a bar at 6th Avenue and 42nd Street and he carried the Wakely surname. With this new information, I was able to verify that Erin is a descendant of one of Jimmy’s siblings.

Jimmy Wakely’s Passport Photo January 1920

James “Jimmy” Wakely was born on 25 November 1850 in Brooklyn, New York. As a teenager, he worked odd jobs for the “sporting men” and politicians in Brooklyn. At the age of 19, Jimmy was already working as a bartender in Manhattan and shortly thereafter he opened a small gambling house over a saloon on West 29th Street where many of the city’s boxers, or pugilists as they were called at the time, hung out. Running the gambling room soon earned him enough money to open his first bar (a.k.a. saloon), which was located on 31st Street. This was also the time when he began brokering prizefights. By 1885, he owned and operated his saloon at the intersection of 6th Ave and 42nd Street in the Tenderloin district.

In a time before boxing management became what it is today, Jimmy was known as a backer and would support his fighters by fronting prize money before the match. He would get a portion of the winnings if the fighter he backed won, but could stand to lose money if the fighter lost. As the sport of boxing progressed, he was also referred to as a manager and would actively confer with his fighters on what to do and who to fight. Most notably, he backed and advised the infamous, John L. Sullivan (a.k.a. The Boston Strong Boy).

The National Police Gazette described Wakely as:

…a man who has had no end of experience in bringing saugunary pugilists together in out of the way places where they could pummel each other to their hearts’ content without any fear of interruption…

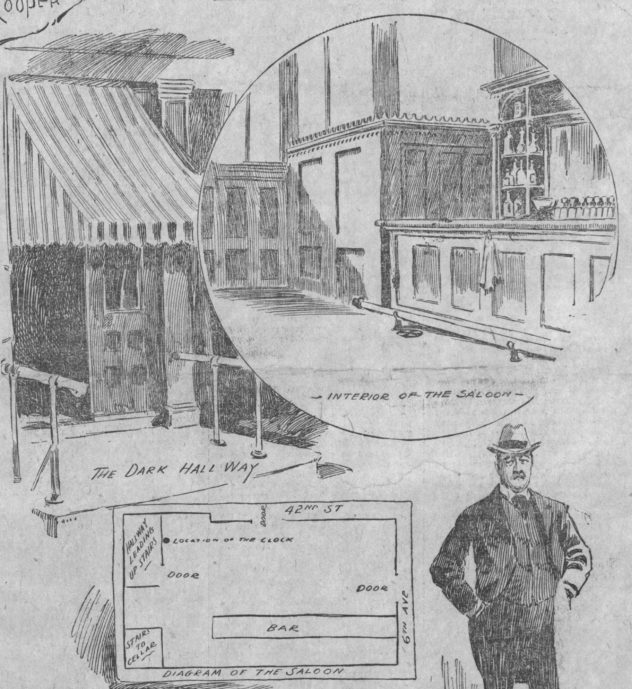

Wakely’s Saloon

Drawing of Wakely’s Saloon from the New York Journal 25 November 1896

Jimmy Wakely’s most famous saloon was located at 42nd and 6th Avenue, across the street from Byrant Park. It was a hub of activity for some of the most prominent prizefighters. At the time, the neighborhood was known as the Tenderloin and it was a considered the red-light district where drinking, gambling, and fighting men liked to frequent. The interior was described as a rather plain establishment except for the painting of horse heads on the ceiling and the large mural of horses behind the bar.

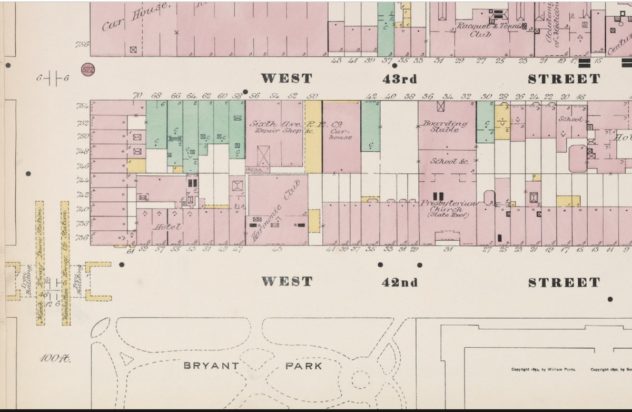

1890 map showing the location of Jimmy’s Saloon. Source: “Manhattan, V. 4, Double Page Plate No. 81 Lionel Pincus and Princess Firyal Map Division, The New York Public Library.

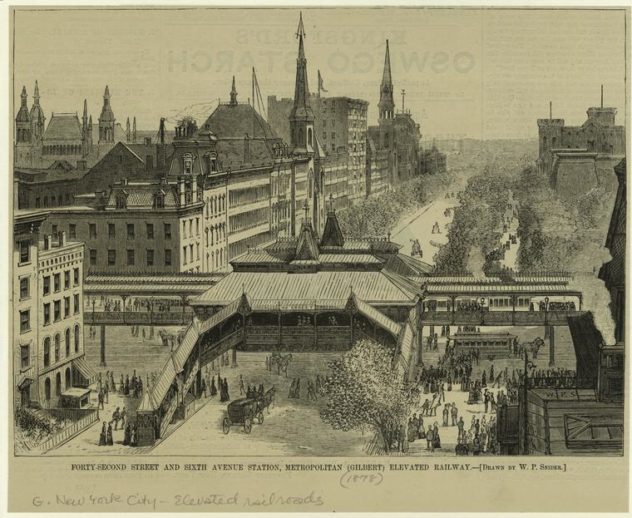

This drawing from 1879 depicts the corner where Wakely’s saloon was located just before he acquired it.

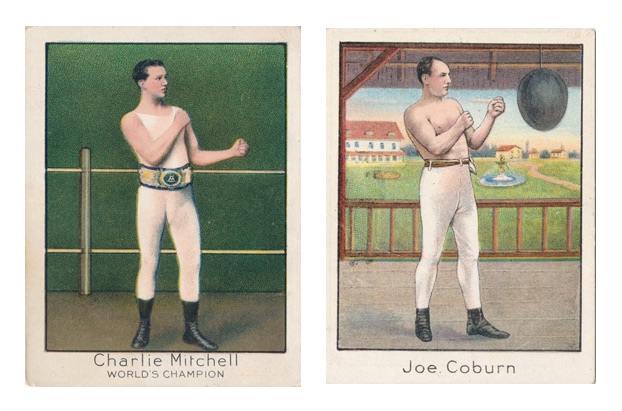

With having a bar full of men who like to fight and drink, it was inevitable that there would be some conflicts. One fight between the pugilist Joe Coburn and a large unnamed man was described in detail in The Sun newspaper:

Mr. Coburn walked over as gracefully as though dancing a prize minuet and, seizing his large friend by the coat collar, before the latter could cease laughing, gave the onlookers a very clever imitation of how belligerent billygoats settle their differences. – The Sun, Friday, 18 January 1889

In 1893, the London prizefighter Charley Mitchell entered Wakely saloon, where he was clearly not welcomed, and after using an “opprobrious epithet” he was hit over the head with the bartender’s siphon and knocked out cold.

Jimmy Wakely himself was even implicated in a fight against the great boxer he once managed, John L. Sullivan. It’s believed that a drunken Sullivan blamed Wakely for drugging him before his loss in the ring to the Gentleman Jim Corbett. Wakely was so enraged by the accusations, that he punched Sullivan in the face sending him to the ground and then kicked him in the eye leaving him with a black eye. It was said that this fight was the falling out of the two partners and friends and that they never spoke to each other again. Although it’s important to note that the way the story was written about in the paper it reads more like a gossip column than a factual depiction of events. In 1893, Wakley was also accused of knocking a blind and elderly woman down outside of his saloon and then kicking her, but he was later acquitted of these charges by a jury who thought she made up the story.

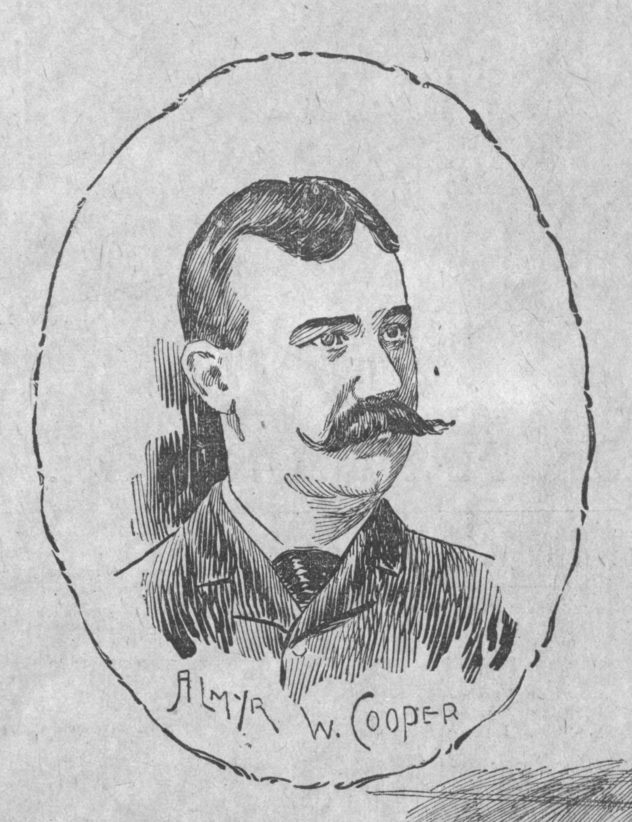

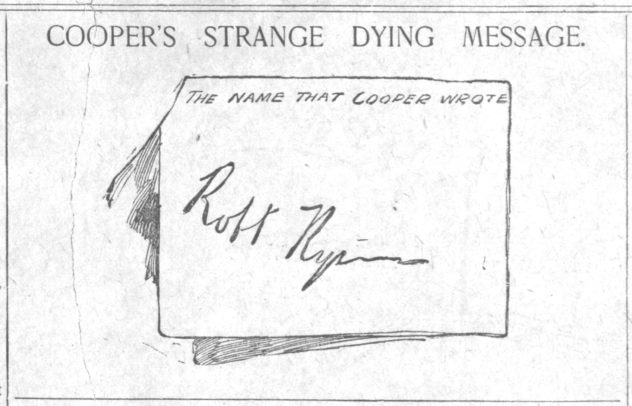

The saloon was even the center of the investigation of the mysterious death of the reporter, Almyr W. Cooper in 1896. On the night of November 5th Cooper was taken to Roosevelt Hospital from Wakey’s Saloon with what first appeared to be a fractured jaw. Eddie Robinson, the bartender on duty at the time, said that Cooper had some sort of epileptic seizure and fell down and hit his head on the bar and that Wakely demanded that the unconscious man be dragged into the alley while they called the ambulance. Another bartender, James Connelly, said that Cooper came into the bar, ordered a drink, and then passed out slamming his jaw on the foot-rail of the bar. He was then taken outside and the ambulance was called. Both bartenders insisted there was no fight or anyone who could have assaulted Cooper inside the bar.

The story takes an even more unusual turn, when reportedly on his deathbed, Cooper was trying to tell his brother-in-law the name of the man that attacked him. He was unable to speak clearly, but it sounded he was saying it was a reporter for The Herald was responsible for his injuries. He was then given an envelope and pencil and scribbled the name of the person, but it was indecipherable. In the days after his death, his sister received an anonymous letter which stated Cooper’s death was not an accident, but rather murder, and the autopsy revealed he not only had a broken jaw but also a fractured skull. It was later believed that he was assaulted on 6th Avenue before going into Wakely’s Saloon and collapsing after ordering a drink.

Cooper’s widow, the actress Isabelle Evesson, continued to find out who was responsible for her husband’s death, but it was never resolved.

Wakely the Gambler

In addition to being a hub of activity for fighters, Wakely’s Saloon was also a well-known “pool room” where men would go to wager on horse races and other sporting events. In 1902, he was the target of an undercover sting operation. The police officer placed a bet with the bartender on the first floor of the saloon. The slip of paper with the bet along with the money was sent up to the second floor where bets were registered and money was kept. If the person won, they could return later that day to claim their prize.

The detective returned in the evening where he witnessed the register of bets and money come down from the second floor to the saloon when he then pulled out a warrant and seized the book. However, Wakely apparently had a way with judges because by late November, Judge Wyatt threw out the case. Wakely argued that the box of money was simply there to pay out the fighters that he managed.

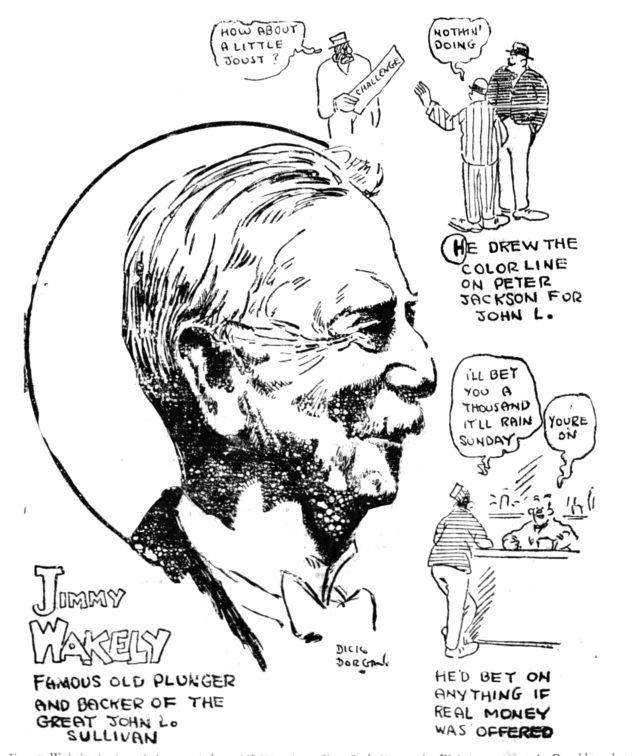

Wakely himself was also a notorious gambler. In a syndicated cartoon published in several newspapers, it described Wakely as a “Plunger” or someone who is known to frequently bet on sporting events. The cartoon further stated that he “would bet on anything if real money was offered.”

In the summer of 1900, there were rumors published in a newspaper that Wakely lost $20,000 (nearly $600,000 in 2019) in a single hand of during a forty hour game of poker on a bobtail flush. He was so indignant of these accusations that he went to set the record straight in a new article. It stated that Wakely “is noted for his willingness to bet on anything from a prize fight to a wheat deal…” Wakely wasn’t so angry that the article stated that he lost, but rather that it falsely claimed he bluffed on a poor hand of cards. In his own defense he wrote:

I wish it understood that I am somewhat over seven years old. Also, I have played cards and gambled in other ways for more than a few brief moons. I flatter myself I know that value of poker hands, and if I ever reach the stage where I become so imbecile as to try to force a bluff when I draw a card to a bad flush and don’t fill, tow other men each draw one card and the fourth stands pat, then I hope they will ship me to Bloomingdales with all possible speed. – The Burlington Evening Gazette 13 July 1900

John L. Sullivan

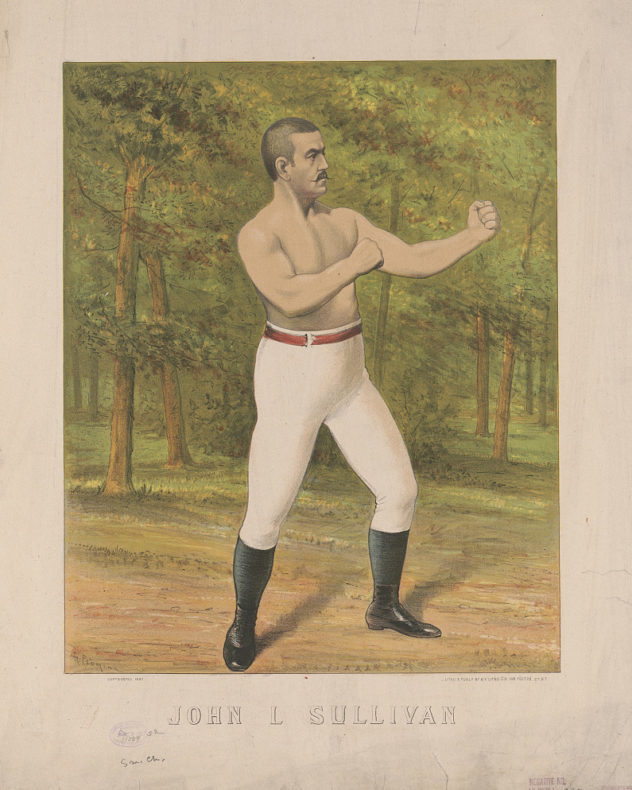

In addition to running a saloon where fighters were known to congregate, Jimmy Wakely is most well-known for being the backer and one of the managers of the infamous John L. Sullivan.

John L. Sullivan, ca. 1887. Nov. 3. Photograph.

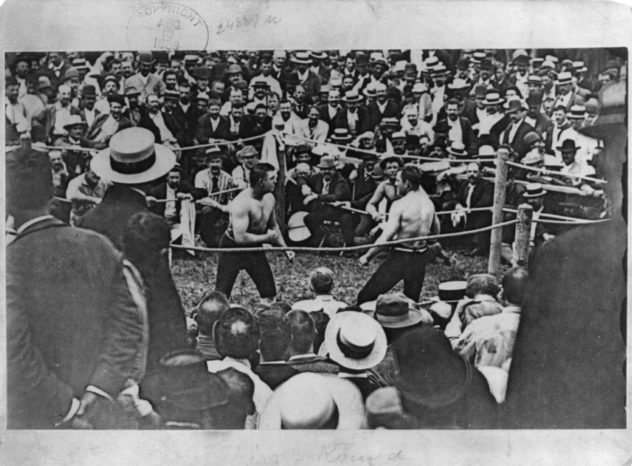

Sullivan was involved in the last fight that used London Prize Ring Rules before bare-knuckled boxing was completely outlawed and fights were to be conducted under the more civilized Marquess of Queensberry Rules which among other things required that fighters wear proper gloves.

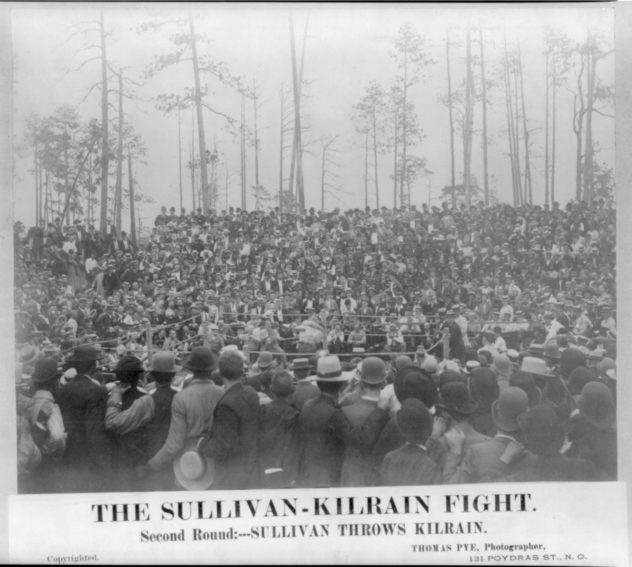

The bare-knuckled match took place in Richburg, Mississippi on 8 July 1889. Arrangements for the fight began in April 1889 when a fundraiser was held to that raised $20,000 for John L. Sullivan in the fight. Wakely was interviewed about the arrangement of the fight and in front of the reporter he pulled out a wad of cash from his coat pocket that was “as thick as Sullivan’s bicep.”

John Lawrence Sullivan, -1918, in clinch during Jake Kilrain fight, 1889.

In the day’s leading up to the fight, it was unclear if and where it was going to be able to happen. The governor of Mississippi was adamant in enforcing that law that stated bare-knuckle boxing was illegal and that the fighters, backers, and spectators were all liable to be arrested. That didn’t seem to deter anyone as both Sullivan and Kilrain made it to the fight and were watched by over 3,000 spectators, many of whom couldn’t even see the ring.

The fight was brutal and lasted 75 rounds over two hours and 18 minutes. In the end, Sullivan was victorious and Wakley won big. Sullivan, his trainer, and two other backers were arrested on the way back to New York after the fight but were eventually released because while bare-knuckled boxing was illegal, it was still a misdemeanor and he couldn’t be extradited back to Mississippi. During his run as a prizefighter, John L. Sullivan was undefeated with most of his fights resulting in a win with a few draws. For a time this proved to be lucrative to his backers, especially Jimmy Wakely. That was until Sullivan’s final fight.

The Night Wakely Lost it All

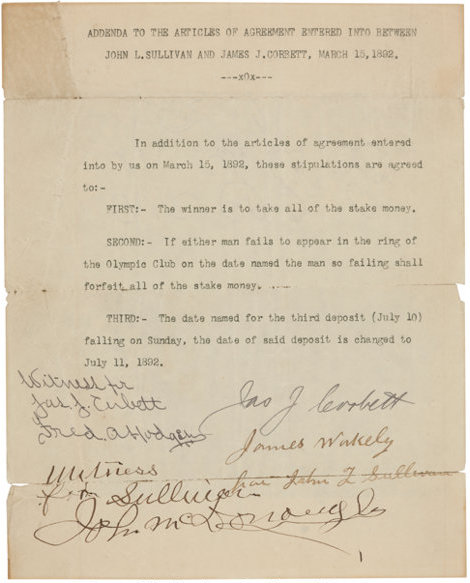

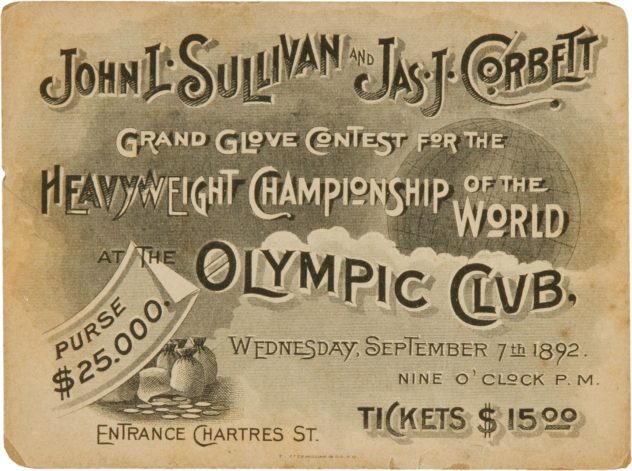

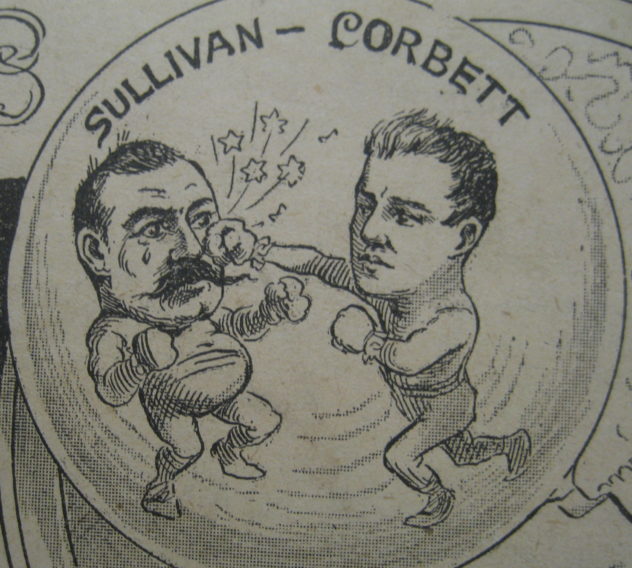

Part of Erin’s family legend is that Wakely lost the family’s entire fortune in a fight and that’s mostly true. John L. Sullivan was undefeated until his last fight. In 1892, it was decided that 34-year-old Sullivan was going to fight 26-year-old Gentleman Jim Corbett. The fight was arranged and the articles of agreement were signed by Wakely on Sullivan’s behalf on 15 March 1892. The fight had a stake of $20,000 and a purse of $25,000, meaning the winner would get a sum of over $692,000 in today’s dollars.

Articles of Agreement for the Sullivan and Corbett match with Wakely signing for Sullivan.

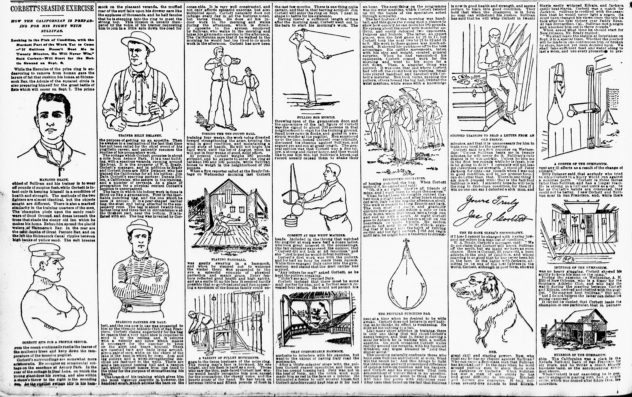

As soon as the details of the match were settled, the big fight was a sensation in newspapers. The summer before the fight The Sun published what can only be described as the first Rocky-style training montage, complete with a trainer in suspenders, medicine balls, elaborate exercise machines, and a dog named Ned.

Newspaper Story Detailing Corbett’s Traning for the Fight

The fight took place on 7 September 1892 at the Olympic Club in New Orleans at 9pm. In the hours leading up to the fight, there was still rampant betting, including Wakely who was placing additional bets on his man, Sullivan, the undefeated favorite.

Many newspapers gave a detailed round-by-round description of the match. The fight lasted 21 rounds and by the last round Sullivan was bleeding heavily and Corbett landed the final blow on his jaw to render him unconscious leading to his victory. Although he was defeated, Sullivan seemed to be a good sport as once he regained consciousness he shook Corbett’s hand and went to the center of the ring to make a small speech. He stated:

“Gentlemen, all I’ve got to say is, I stayed once too long, I met a young man, I’m glad the championship remains in American with one of her own people.”

There was no doubt that Wakely lost a lot of money in that fight. The Time-Picayune was documenting how much many famous men lost of the fight and instead of listing an amount for Wakely it merely stated that he “of course lost heavily.” And later newspaper accounts speculated that it was upwards of $25,000 ($690,000 in 2019) in a single night.

Wakely’s Decline After the Loss

By 1906, his bar was being shut down as the whole block was being slated for renovation. He moved his establishment down the road on 43rd street. The closure was commemorated in the New York Times and his friends even wrote a poem to eulogize the moment, which was wired to John L. Sullivan.

It’s 23 for Jimmy;

His joint is on the bum

But we’ll carry him up the street a block

An’ still hit up his rum.

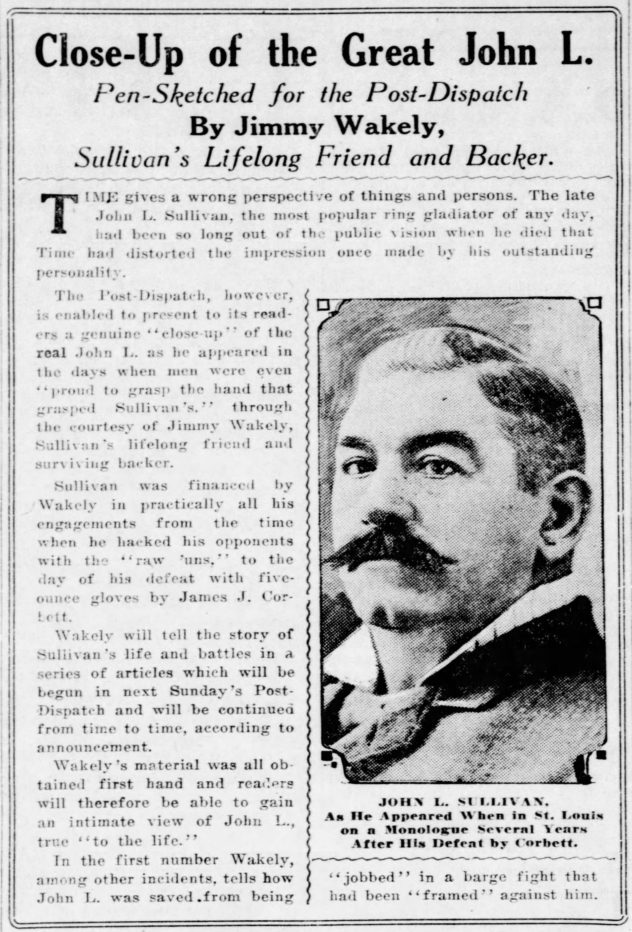

Whatever falling out between Sullivan and Wakely after the fight didn’t last forever because after Sullivan’s death in 1918 Wakely wrote a series of syndicated articles and eulogies remembering his time managing the great fighter.

St. Louis Post-Dispatch – Friday, 22 February 1918

However, it seemed like Wakley never financially recovered from his big loss and his last saloon on 43rd Street was closed just a couple of years later. By 1909, he was removed from out of the Brewer’s Association and the James Everard’s Breweries foreclosed on his saloon.

In 1912, The Sun reported that although at one time he was worth over a quarter million dollars Wakely was now sick and broke. Jimmy had suffered a stroke causing him to pass out on the sidewalk of 42nd street after exited a Turkish bath and was sent to recover in a nearby sanitarium. Although his friends speculated that if he called in all of his debtors he would have about $200,000, but instead they pitched in money for the sick and destitute man. The episode was so severe, that one newspaper even reported that he had a fever of 105 that would likely kill him.

In his old age, it was said that he was seen around town squabbling with younger gamblers over a small sum such as $50. The old men of the Tenderloin reminisced about how generous Jimmy had been the height of his fortune recalling the one morning where he and some of his men went around Byrant part giving money to all the homeless that slept there so they could have a hot breakfast. Another man remembered how he once saw Jimmy lose $30,000 in one sitting while playing the card game faro.

His condition remained bleak. In 1920, he even traveled to Cuba in the hopes of improving his health. Shortly before his death, another article was published in the Boston Globe asking for financial help for the ailing and aged sporting man. The article stated that “Jimmy Wakely is old and broken, broken in health, and according to reports, in pocket.” It detailed that while Wakely was once one of the “prize ring aristocrats” he was always generous with his winnings and never hesitated to help out the less fortunate. The article ends with a plea for readers to not forget Wakely and if one couldn’t help him out financially, then they could at least drop him a line and let him know he wasn’t forgotten.

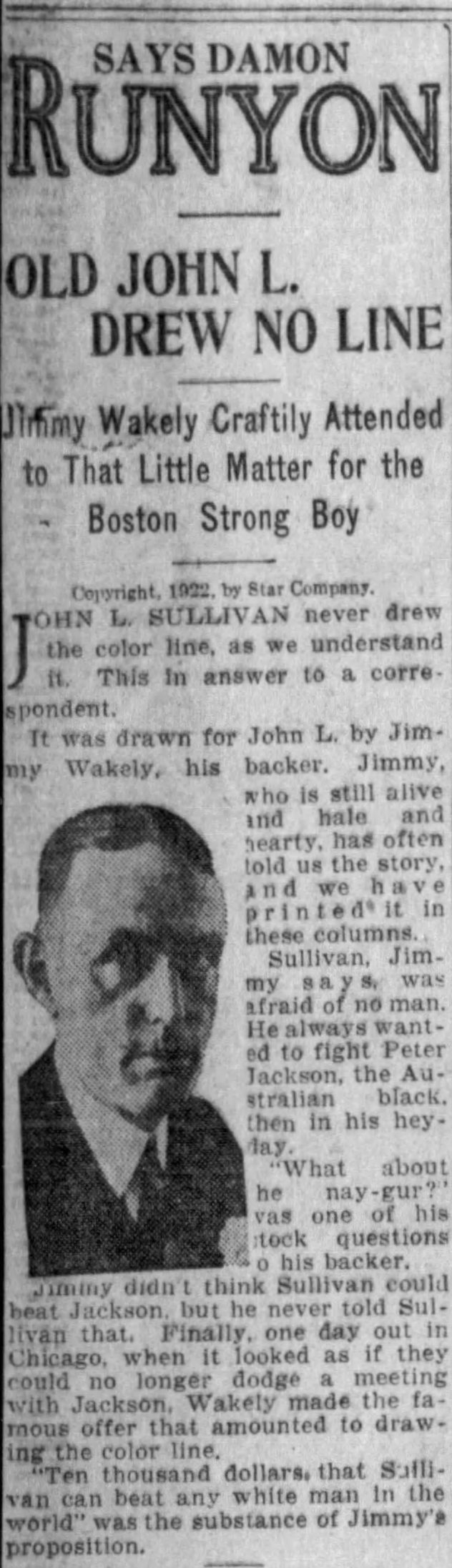

Late in his life, Wakley befriended the reporter and writer Damon Runyon on as he was interested in publishing stories of the old pool rooms and prizefighters. Runyon was the first to publish that it was Wakely who convinced John L. Sullivan “draw the color line” and refuse to fight the African American boxer Peter Jackon. However, the decision had nothing to do with race, but rather because he was convinced the still undefeated Sullivan would lose against the stronger and more athletic Jackson.

Two of Runyon’s stories of old New York were later adapted for the Broadway musical hit Guys and Dolls. It is likely that some of Wakely’s own stories were the inspiration for Runyon’s fictional tales of old Manhattan.

Wakely’s Death

Jimmy Wakely died on 3 July 1924 at St. Vincent’s Hospital in New York. He never recovered from his financial loss and many thought his penury was the result of never following up on any of his debts. He would lend money to his friends and well-wishers that were down on their luck, collect the I.O.U. notes but never collected they money or accrued any interest. It was said that upon his death, his family burned the notes as Jimmy never had the intention of collecting the money anyway.

Damon Runyon’s Fundraiser for Jimmy Wakely

This is one part of Erin’s family legend that I thought would be difficult to prove, however, in an article that Runyon had written about Wakely’s death it stated that:

Some of Wakely’s friends yester started a little subscription as a sort of memorial Wakely, the money to be turned over to his family. The writer has been requested to take charge of this fund. You gentlemen of the old school who remember Wakley in the days of his influence, who recall his generosity, his ready response to every worthy call will wish to contribute to this fund. Checks may be sent to the writer who will turn them to the proper source.

Another article that detailed his memorial and funeral stated that it wasn’t until after his death that the depths of his financial troubles were fully exposed. In his later years, his rent and living expenses were paid almost entirely by friends. It was stated that one of his closest friends, Jack Dunstan, arranged for another collection to cover the costs of a proper funeral for Wakely. This is likely the fundraiser that Erin’s “lace-curtain” Irish wanted nothing to do with.

The Verdict

From this research, it’s clear that Erin’s Granny is NOT a liar. This is probably the most truthful of family legends I’ve ever researched. The only detail that was wrong was the nickname. With that said, in all my research I did see several articles that referred to him as “Brooklyn” Jimmy Wakely, but after the 1880s the “Brooklyn” was dropped. Later accounts of his life also referred to him as one of the “Great old sporting men of Broadway.” Perhaps this is the origin of the nickname.

Research Notes

This post is almost as long as Sullivan and Kilrain’s 75 round fight. I found so much information about Wakely, it was hard to condense it into one story. I also relied heavily on newspapers to learn about Wakely’s interesting life. The genealogist in me know that newspapers are secondary sources and to be wary not everything published in the papers is always true. In this case, I’m certain that were more than a few details that were embellished.